Ways of Publishing #2 / June 5th, 2021

Ways of publishing #2

Saturday 5th June, 2pm-8pm

2 to 6pm: Workshop open to students with Agathe Boulanger, Signe Frederiksen and Jules Lagrange, authors of Ce que Laurence Rassel nous fait faire, Paraguay (2020)

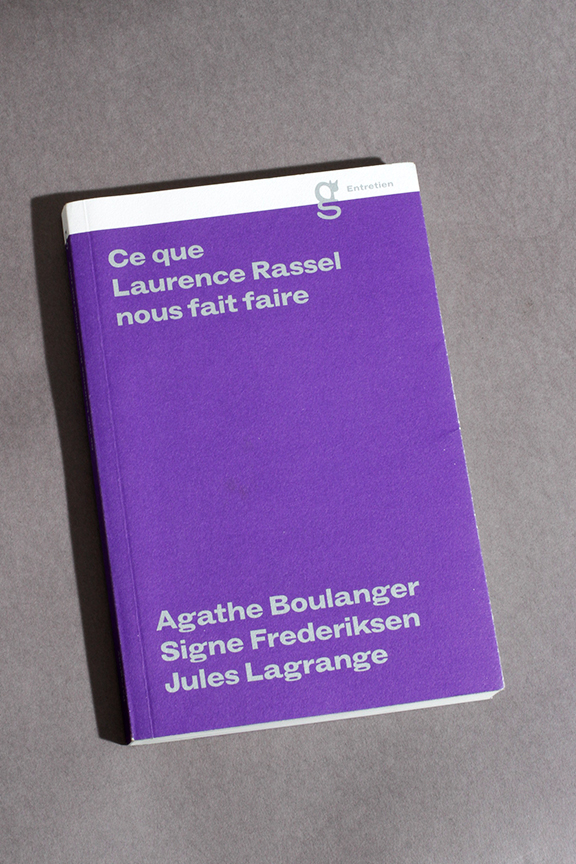

Agathe Boulanger, Signe Frederiksen, Jules Lagrange, Ce que Laurence Rassel nous fait faire, Paris, Paraguay, 2020 © Julien Richaudaud

What are we doing here? is the fundamental question that Jean Oury, French psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, founder of the La Borde clinic, was constantly asking himself, as an ethical position, a way of situating oneself, without which one finds oneself absorbed by habits, the "ça va de soi" (”it goes without saying”), passivity.

Based on the book Ce que Laurence Rassel nous fait faire, this writing workshop is open to art school students. It intends to think together about the institutional experiences we face in the art world, through the formats of the interview, the discussion group and the mental journey. We will question together where we come from, what we are doing there, and which institutions we want to inhabit.

This book of interviews with Laurence Rassel, director of the Graphic Research School (Erg) in Brussels, presents a practice inspired by feminism, free software, science fiction and institutional psychotherapy. More than a biography, it is a tool to reflect on the ways of working in institutions in the art world.

The artists Agathe Boulanger, Signe Frederiksen and Jules Lagrange met in the post-graduate program of the École des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. Their shared interest in pedagogy, the working conditions of artists and institutional critique led them to conceive this book of interviews with and about Laurence Rassel. Through writing and performance, Agathe Boulanger explores different forms of affective heritage, and investigates how conflicts shape relationships and how they can be resolved. Signe Fredriksen writes and stages performances in a manner that challenges traditional divisions between art and audience, and she works as an occasional publisher. Jules Lagrange is interested in the degrowth movement and his works revolves around vernacular craftmanships and the feelings they can trigger.

Laurence Rassel was born in 1967 between Belgium, France and Luxemburg, in a region marked by the decline of the steelwork industry and which she left in the early 90s to enter an art school in Brussels. There, struck by class discriminations and uncomfortable with the mythical figure of the artist that was promoted by art schools at the time (a naturally gifted genius), she felt the urge to educate herself differently. Cyberfeminism, collective work, survival in precarious economic conditions, and above all friendships, became the foundations of her practice. She began volunteering at Constant in Brussels where she found inspiration in the open-source model. This experience has led her afterwards, when she became director of the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelone, to imagine how the archives of a museum could be made more accessible to the public. She is now the director of the ERG school in Brussels where she promotes ways of working based on collaboration, process and transmission – an autonomous school where the notion of authority is challenged and where every student can act on the institution itself. As a director, curator, thinker and agent of change, Laurence Rassel has been living several lives at once, and tries to provide others with everything that she lacked.

6 to 8pm. L’oxymore : un polar bizarre. Reading and presentation by Fanette Mellier and Joseph Schiano di Lombo, authors of L’Oxymore, Éditions B42 (2021).

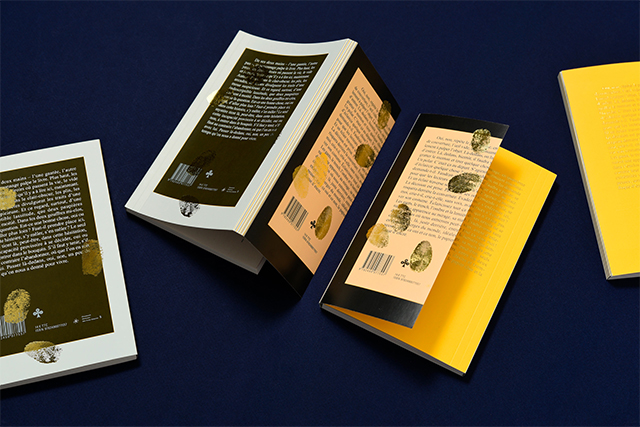

Fanette Mellier, Joseph Schiano di Lombo, L’Oxymore, Paris, Éditions B42, 2021

In order to understand what this detective novel is, you have to start by saying what it is not; that is, a detective novel. Would L’Oxymore be an anti-thriller in this case? Hardly.

Not a drop of blood flows in these pages, not a gram of drugs circulates, not even a little rape on the go. The investigator, the commissioner, the police officer, the drug dealer, the sulphurous or abused women, everyone has disappeared. And the purpose of this book is certainly not to find them.

Is it possible to write a detective story without an investigation? Or rather – since in literature anything is possible if one lacks sufficient reverence for the rules – how? To what extent and by which feints can we designate as a detective novel a book that denies us not only the elucidation, but even the plot itself? Such a direction is certainly a far cry from the comforting horizons to which the genre is destined. In fact, to refuse the police plot is to mourn the return to a harmony that existed before the fall. It is finally to undo the square reason, that of the meticulous investigator, to consent to the beauty of the emptiness on which we are agitated, and to yawn before the provisional resolution of enigmas by which our need for knowledge is so easily titillated.

Share